Path to Diagnosis: Part IV (Breathing)

/Continued from Diagnosis: Part III (Traction)

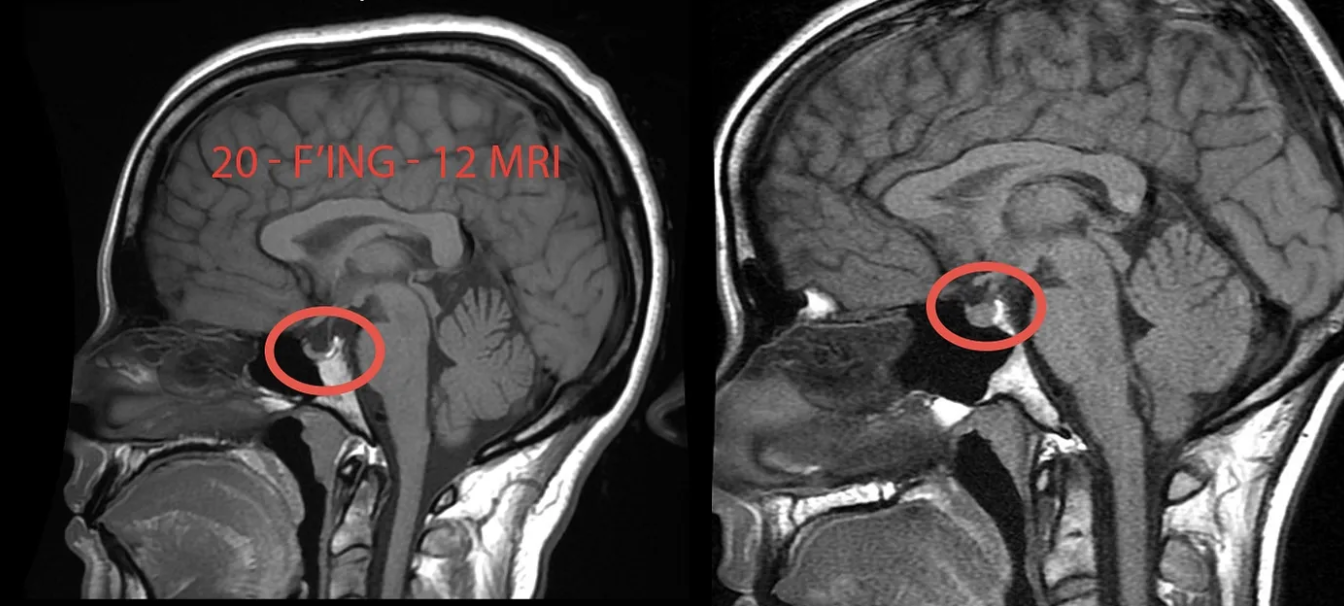

I woke up in recovery with an intracranial pressure bolt screwed into my head. It was late afternoon. I remember the warm light streaming in through the green partition curtains. They struck me as beautiful. I don’t know if they actually were. It could have been the anesthesia wearing off or the pain meds kicking in. Or maybe my entire memory of that moment was colored by the peace I felt. The peace that I finally knew. I knew from the traction testwhat had been causing many (perhaps all) of my symptoms for the last seven years.

Or maybe when you have a bolt sticking out of the top of your head, and the highlight of your day is when the chocolate pudding comes around, your sense of aesthetics…changes.

Omar was visibly unnerved by my appearance and made many jokes about trepanation and releasing bad spirits. They took me from recovery to the ICU, where I fell asleep. Every once in awhile, the machine would alarm but I couldn’t see the readings and figured that tomorrow, they would tell me what it all meant.

In recovery after my intracranial pressure bolt was inserted in my skull. It continuously measured the pressure in my skull for 24 hours.

In the morning, my neurosurgeon came to the ICU. I am used to a certain style of medicine: run a bunch of labs, everything comes back normal (or doesn’t), make some guesses and give a pill. I am used to the bureaucratic execution of the standard of care, which can often prevent doctors from observing the empirical world as it exists, right in front of their eyes. This kind of care can sometimes lead to some pretty silly situations, such as the PCP who kept suggesting that a symptom I had was being caused something that had occurred after the symptom started. Or all of the many times I have presented with severe neurological symptoms and simply had my doctor, when he failed to explain them, discount that they were happening at all. Doctors send you out for tests, they read some piece of paper (the lab test, the radiology report) that comes back. You (and they) hope the paper tells them something actionable. Otherwise, they throw you to the curb and you are left to complete the whole dispiriting, impoverishing cycle over and over and over again. Dr. House is a myth. They almost never say, “I don’t know, I can’t help you.” Rather you most often hear, even (especially?) if you’re a young woman who has been living in a bed for years, “there’s nothing wrong.”

Now, in some ways my neurosurgeon’s project was not radically different from any other specialist. His aim was to figure out whether my case fit within the purview of his sub-sub-sub specialty: in other words, to decide whether or not he could help me. He had, through a depth of experience, developed a skill of pattern recognition of the kind of structural, neurological complications patients like me can develop. This kind of skill, when the right expertise meets the right case, can feel like magic; like this is how it’s supposed to work. It’s an experience I hope every patient gets to have.

Being diagnosed with craniocervical instability was entirely different from anything I’d experienced before in medicine. Yes, my surgeon took objective measurements, but he also observed. He looked at the patient in front of him and sometimes perturbed the system to see what would happen. He did not just take measurements, he took them over and over (and sometimes ovveerrrrrr) again. It was as though he was flipping a coin to see how many heads he would get. In other words, he ran experiments.

This is why, as someone who almost got a master’s degree in statistics before my body fell apart, I came to trust my surgeon and my diagnosis and the possible good that might come with surgery. It was because my surgeon was not only a doctor, his approach was like that of a scientist. He worked very hard not to lie to himself.

My neurosurgeon had me take off my cervical collar. He lowered my bed so that I was lying supine, putting pressure on the back of my head, the precise position guaranteed to cause my apnea. When I had apnea while in this position, I was also immobilized: I could not breathe, I could not blink, I could not move anything but — I think occasionally, not always — my eyeballs. The closest thing to it is a kind of temporary locked-in syndrome. With each breathing cycle, I would have periods of total immobilization and apnea for tens of seconds, then gasp for breath, then it will start all over again. When in this state, no matter how hard I tried, I could not get my diaphragm or chest wall muscles to move. The first few times it happened, Omar and I went through dozens of cycles over the span of as long as an hour, until finally we realized it was related to how I lay on my head: on my back, I could not breathe. On my side, I (mostly) could.

I hated going through it, that cycle of stop breathing, gasp-gasp-gasp, stop breathing, gasp-gasp-gasp. It’s given me insight into what it might feel like to be dying, or drowning, insight frankly I wish I did not have.

At least my neurosurgeon and I were now on the same page that this was actually happening, that it might be related to the craniocervical instability and the cranial settling he had just diagnosed, and he was here to find out why. “Do your worst,” I thought, and maybe we’ll finally get to the bottom of this.

He had me lay there for what seemed like an interminable amount of time, making me go through what I had been experiencing in private for months. This time, though, I was hooked up to a machine. This is how the pattern went: not breathing, alarm! alarm!, gasp-gasp-gasp, not breathing, alarm! alarm!, gasp-gasp-gasp, not breathing, alarm! alarm!, gasp-gasp-gasp. I remember thinking, “how many times is he going to make me go through this? I tried to study his face, as much as one can when one is barely breathing and cannot really move anything but one’s eyes, if that. “I keep hearing the alarm,” I thought. “You keep staring at the machine,” I thought. “Do you see something? Does it make sense? Do you believe me? Did you figure it out? Will you help me? Will you throw me to the curb?”

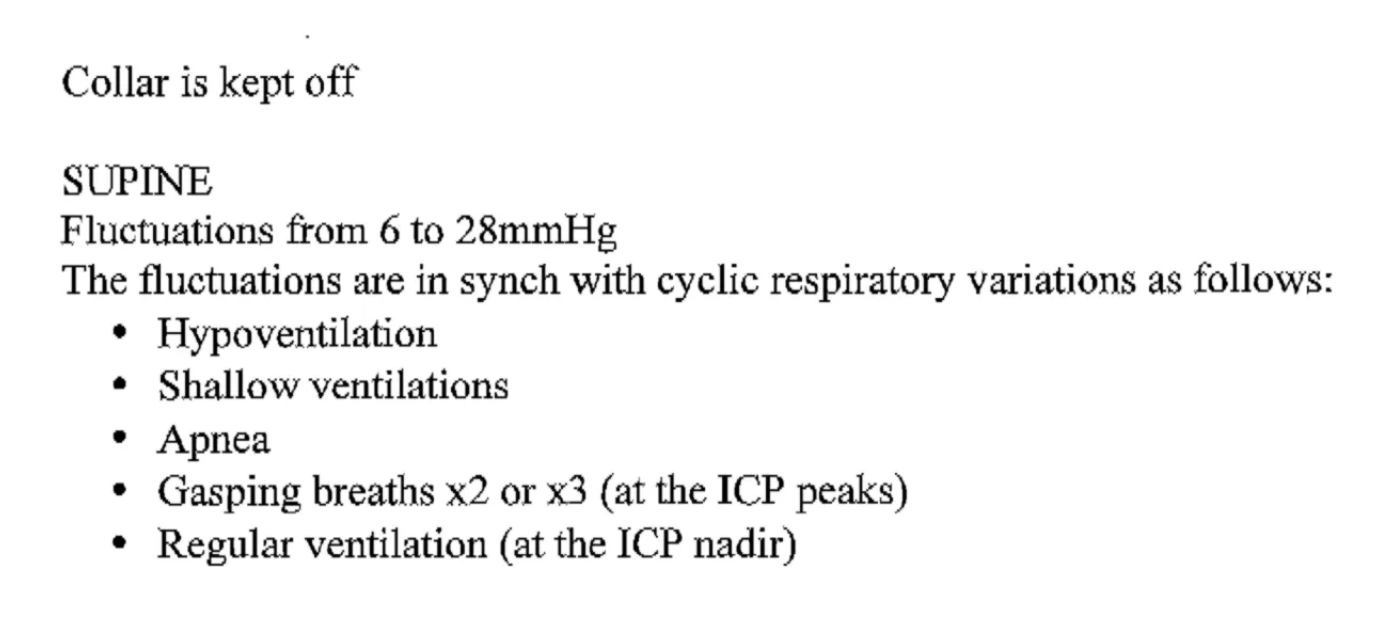

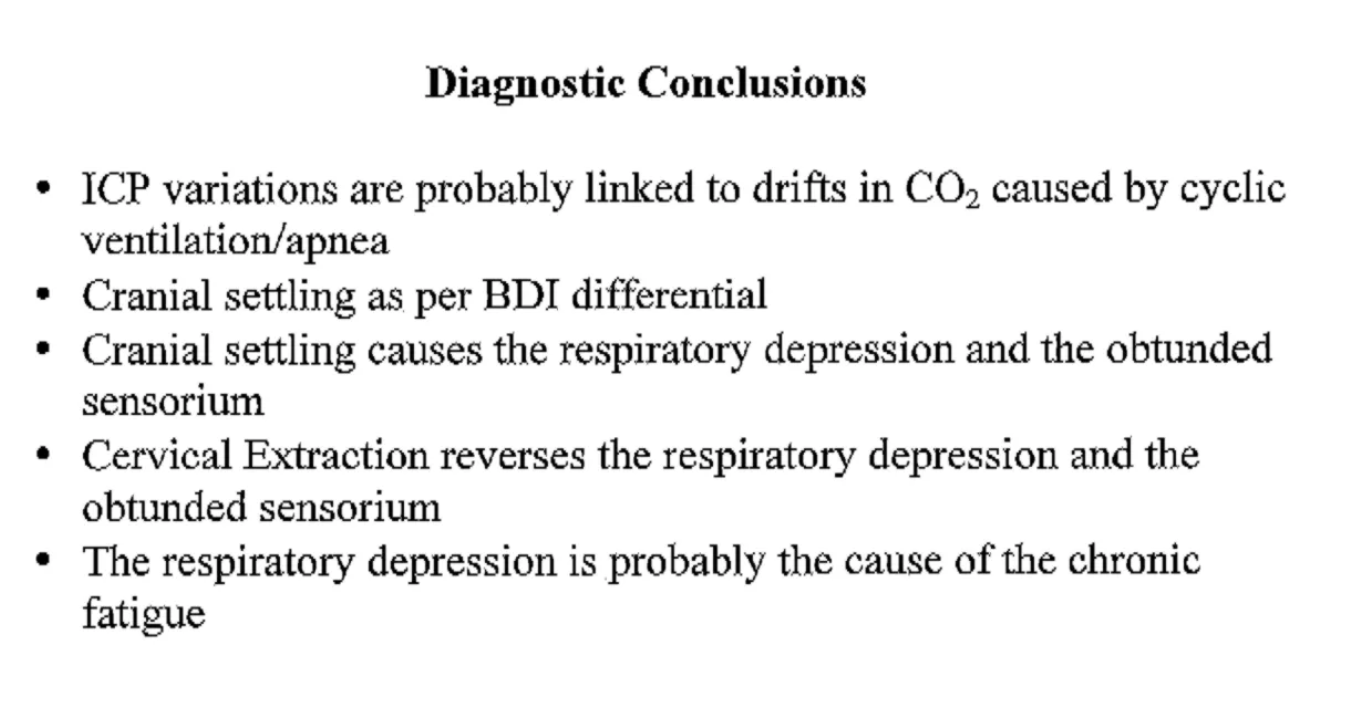

Here is what he later wrote on my chart:

Being diagnosed with craniocervical instability was entirely different from anything I’d experienced before in medicine. Yes, my surgeon took objective measurements, but he also observed. He looked at the patient in front of him and sometimes perturbed the system to see what would happen. He did not just take measurements, he took them over and over (and sometimes ovveerrrrrr) again. It was as though he was flipping a coin to see how many heads he would get. In other words, he ran experiments.

This is why, as someone who almost got a master’s degree in statistics before my body fell apart, I came to trust my surgeon and my diagnosis and the possible good that might come with surgery. It was because my surgeon was not only a doctor, his approach was like that of a scientist. He worked very hard not to lie to himself.

My neurosurgeon had me take off my cervical collar. He lowered my bed so that I was lying supine, putting pressure on the back of my head, the precise position guaranteed to cause my apnea. When I had apnea while in this position, I was also immobilized: I could not breathe, I could not blink, I could not move anything but — I think occasionally, not always — my eyeballs. The closest thing to it is a kind of temporary locked-in syndrome. With each breathing cycle, I would have periods of total immobilization and apnea for tens of seconds, then gasp for breath, then it will start all over again. When in this state, no matter how hard I tried, I could not get my diaphragm or chest wall muscles to move. The first few times it happened, Omar and I went through dozens of cycles over the span of as long as an hour, until finally we realized it was related to how I lay on my head: on my back, I could not breathe. On my side, I (mostly) could.

I hated going through it, that cycle of stop breathing, gasp-gasp-gasp, stop breathing, gasp-gasp-gasp. It’s given me insight into what it might feel like to be dying, or drowning, insight frankly I wish I did not have.

At least my neurosurgeon and I were now on the same page that this was actually happening, that it might be related to the craniocervical instability and the cranial settling he had just diagnosed, and he was here to find out why. “Do your worst,” I thought, and maybe we’ll finally get to the bottom of this.

He had me lay there for what seemed like an interminable amount of time, making me go through what I had been experiencing in private for months. This time, though, I was hooked up to a machine. This is how the pattern went: not breathing, alarm! alarm!, gasp-gasp-gasp, not breathing, alarm! alarm!, gasp-gasp-gasp, not breathing, alarm! alarm!, gasp-gasp-gasp. I remember thinking, “how many times is he going to make me go through this? I tried to study his face, as much as one can when one is barely breathing and cannot really move anything but one’s eyes, if that. “I keep hearing the alarm,” I thought. “You keep staring at the machine,” I thought. “Do you see something? Does it make sense? Do you believe me? Did you figure it out? Will you help me? Will you throw me to the curb?”

Here is what he later wrote on my chart:

The respiratory depression is probably the cause of the chronic fatigue. Now, I have explained to my neurosurgeon more times than I can count that I do not have “chronic fatigue.” I have post-exertional malaise (PEM), the hallmark symptom of my illness. PEM is the worsening of all symptoms after physical or cognitive exertion. I was not “tired,” as he suggested, because the apnea was somehow messing with my sleep. (I sleep just fine.) Rather, I was “crashing,” as many patients call it.

I started to wonder, though, whether my apnea and PEM might in any way be related. Granted, most ME patients don’t have apnea, but my apnea didn’t start until more than seven years after my viral onset. It only started after my thyroid surgery last June, during which my neck was hyperextended. After that surgery, something had happened to my brainstem such that it did not perceive the need to breathe until my CO2 levels would skyrocket well beyond normal. It was like I had a broken thermostat that wouldn’t kick in until the temperature had reached 80 degrees. Everything downstream worked, it’s just that the normal processes weren’t being initiated at the right time.

I had a similar problem with actual temperature. I wouldn’t sweat in the sauna. I was cold when I shouldn’t be. And after my thyroid surgery, I had a period of time when I would stick my hand under the faucet and couldn’t tell what temperature the water was. Perhaps POTS was also a problem of this kind. For sure, the extreme sleep cycle shifts that many patients experience could be something like this, too. If so many of our symptoms were forms of dysautonomia, could PEM (as researchers at the Workwell Foundation recently asserted) be one as well?

Seeing me with my ICP bolt and my red, glowing pulse ox, Omar said “#ourcyborgfuture.”

This concludes my diagnostic journey. My surgeon’s ultimate diagnoses were: Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Mast Cell Activation Disorder (MCAD), Craniocervical Instability, Tethered Cord Syndrome, Adrenal Insufficiency, Dysautonomia, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, and Intracranial Hypertension.

I will share the story of my surgery and recovery, but next, I want to try to explain why I think all of this may have happened to me and how my viral onset (several years after a severe mold exposure) may have triggered my craniocervical instability. We’ll be jumping from what I know about my case to that about which I can only ever make conjectures, but I think from that speculation might come some good questions worth asking.

In the meantime, read all the posts in my CCI + tethered cord series

Read this disclaimer. Crucially, surgery carries risks and it’s important to remember that in medicine, the same exact symptoms can have multiple, different causes. We have no idea how prevalent CCI is in our community and there’s been no research into its relationship with ME. We do know that it is more common among patients with EDS.